Ozzy Osbourne: The Voice That Made Music Out of Fear

28 Oct 2025

Reading 8 min.

By Javi Félez

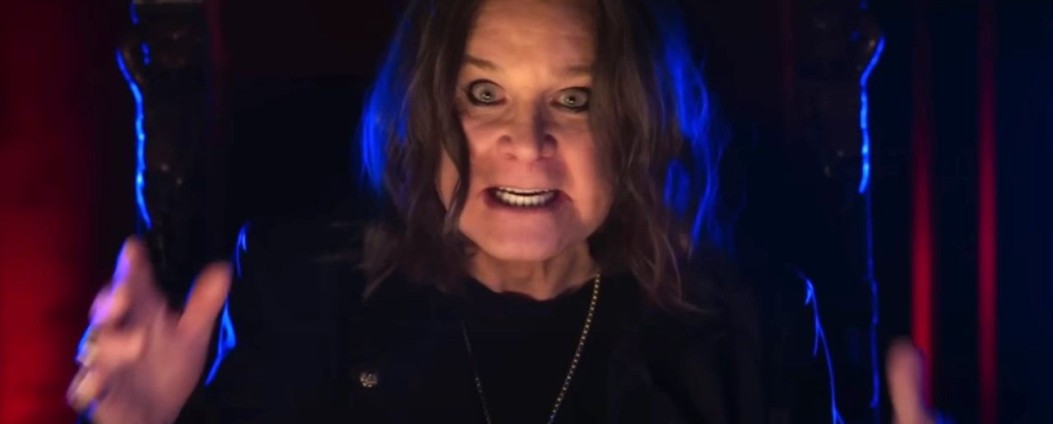

On July 22nd, 2025, one of the most turbulent, controversial, and fascinating chapters in rock history came to a close: John Michael “Ozzy” Osbourne, the unmistakable voice behind Black Sabbath and architect of one of heavy metal’s most iconic and extravagant solo careers, died at the age of 76. His passing isn't simply the news of a man who succumbed, like all of us, to the inexorable passage of time (and excesses of all kinds), but also the twilight of a legend who embodied, with the force of an archetype, the intimate relationship between rock and metal music, horror movies, and the human fascination with the dark, the supernatural, and the unknown.

Ozzy Osbourne wasn't just a song singer: he was a medium, a spokesperson who for more than half a century turned anguish, superstition, and fear into aesthetic material. Where others saw only a provocative spectacle, he recognized a mirror of humanity, a way of transgressing conventions and inviting the audience to confront what's usually relegated to the shadows. His unmistakable voice, nasal and flat, embellished his sonorous prayers like a jester narrating the misfortunes of others with a certain tone of mockery and sarcasm.

Genesis of Darkness

Born in Birmingham, in the industrial heartland of England, Ozzy Osbourne emerged in a bleak urban landscape filled with factories, smoke, and precariousness, which could only fuel a dark sensibility that focused on the negative aspects of life. When he met Tony Iommi, Geezer Butler, and Bill Ward in 1968 to form Black Sabbath, what emerged wasn't just a band: it was the birth of a new aesthetic sensibility, a musical genre that - unlike the optimistic, somewhat banal and lysergic rock of the time - dared to look death, war, and the damned straight in the eye.

The name of the band itself, Black Sabbath, was a poetic statement. Not only did it refer to Mario Bava's film of the same name, released in 1963, but it also embraced the evocative power of film imagery. The influence of horror movies already permeated the band's roots: the first song on their debut album, Black Sabbath, begins with lugubrious bells and a tritone riff - the famous “devil's interval” - to narrate the appearance of a sinister figure in the shadows. It was music that sounded like a spell, like a sonorous nightmare. It was 1970, and heavy metal had just been born with a very simple 3-note DNA.

On later albums, Sabbath expanded on this imaginary world: Children of the Grave offered visions of apocalypse and spectral resurrection as an anti-war parable; Master of Reality played with notions of the invisible and the absolute; Sabbath Bloody Sabbath delved into nightmarish labyrinths... All of this engaged in an underground dialogue with the horror movies of the time, such as the fascination with the satanic after the release of The Exorcist in 1973 or the gothic imagery of Hammer, for instance.

Black Sabbath, with Ozzy at the helm, was not mere entertainment: it was, like good horror, a direct confrontation with the collective anxieties of that era's modernity.

Monsters and Metamorphosis

When Ozzy was kicked out of Black Sabbath in the late 1970s, many considered his career to be over. In fact, it was. However, what followed was the remaking of an even more powerful legend. His solo career never abandoned his somber tone, but rather intensified and dramatized it, turning it into a mass spectacle.

Songs like Mr. Crowley, inspired by the famous occultist Aleister Crowley, not only flirted with the esoteric, but turned it into rock cult material even for those unfamiliar with the subject. Bark at the Moon, with its werewolf and gothic laboratory music video, looked like something out of the Universal Studios of the 1930s, a parable of madness and monstrous transformation. Even titles like Diary of a Madman seemed to come straight out of a library of vintage horror classics.

But the decisive factor was that Ozzy didn't just sing about fictional horrors: he himself became a monstrous creature, a walking legend. The anecdote from 1982 - when he bit the head off a bat thrown onto the stage - was etched into the collective imagination as an act somewhere between grotesque and sacramental, an involuntary performance that made him a liminal figure, halfway between a satanic jester and a priest of excess and depravity.

His music was a continuous tale of metamorphosis: men who become beasts, heroes who descend into madness, addictions that drag them into the abyss, nightmares that torment them in the darkness of the night... The theatricality and gesticulation, the makeup, the howling, and the staging were extensions of the horror film tradition: a carnival of the ominous where the audience both feared and celebrated in communion.

Ozzy Flirts with the Screen

Osbourne's connection to cinema wasn't just about inspiration. He was a passionate viewer and occasional actor, a conscious accomplice to his own myth. He himself acknowledged that The Exorcist left an indelible mark on him: that vision of demonic possession drove him and his Sabbath bandmates to write music that seemed more terrifying than any film. In those words lies the understanding that horror isn't just a storyline, but atmosphere, insinuation, vibration, and sound texture.

His cameo in Trick or Treat in the mid-eighties, playing a television preacher who denounced metal as “satanic music,” was an act of irony in the form of self-reference: Ozzy disguised himself as his own detractors, becoming a grotesque mirror of the puritanical morality that would haunt him mainly during the 1970s and 1980s and which would later be toned down.

Likewise, his most famous music videos - particularly Bark at the Moon - can be considered authentic horror short films, featuring transformations, sanatoriums, tombs, and creatures. They were implicit tributes to the cinematic tradition that had nurtured him, but they were also, in their own way, educational: they introduced new generations to the imagery of classic horror.

His songs, loaded with dark atmospheres, have become a common resource in film and television. Songs like Iron Man and Paranoid have accompanied action and horror sequences, giving them a very effective immediate apocalyptic tone. Recent series such as Netflix's Stranger Things have recycled this iconography: teenagers with Walkmans and Sabbath cassettes, walls covered with posters, and riffs that invoke, in a nostalgic key, the aesthetics of the sinister.

His songs, loaded with dark atmospheres, have become a common resource in film and television. Songs like Iron Man and Paranoid have accompanied action and horror sequences, giving them a very effective immediate apocalyptic tone. Recent series such as Netflix's Stranger Things have recycled this iconography: teenagers with Walkmans and Sabbath cassettes, walls covered with posters, and riffs that invoke, in a nostalgic key, the aesthetics of the sinister.

Satanic Panic and Ozzy as a Scapegoat

In the 1980s, while heavy metal conquered stadiums and pop music shined on neon televisions, a social phenomenon laden with fear emerged: what was popularly known as Satanic Panic. Televangelists, parents' associations, and politicians (remember the famous and unintentionally comical PMRC) found, in the dark lyrics and aesthetics of metal, proof of a supposed demonic conspiracy that seduced young people. Among all those accused, Ozzy Osbourne's face became the favorite target. His spectral voice, his exaggerated gestures, and his public excesses seemed to confirm the role of villain that society sought to point to in order to camouflage its own miseries.

The climax arrived in 1986, when a family took Ozzy to court after the suicide of a teenager, claiming that the song Suicide Solution was a direct invitation to death. The court dismissed the case - the lyrics actually referred to the ravages of alcohol - but Ozzy's image as a corrupter of souls was forever engraved. Like horror movies, which for decades were accused of corrupting audiences, Osbourne embodied the uncomfortable figure who serves as a mirror for collective fears. And so, rather than a musician, he became a scapegoat: the cultural monster needed by society to point out that which is forbidden... (and at the same time consume it with fascination).

Ozzy, an Autobiographical Myth: From Family Reality TV to Tragic Archetype

In the early 2000s, a new stage revealed another side of Osbourne: television. The reality show The Osbournes, broadcast on MTV, showed the musician in his home life, far from the hellish coven of his concerts. There we saw a fragile Ozzy, sometimes comical, confused in his kitchen or babbling incoherent phrases. For some, the series dismantled his myth; but in fact, it actually expanded it.

That household portrait associated him with the tragic monsters of horror movies: the aging vampire, the rejected Frankenstein, or the werewolf tired of his curse. The public saw him not only as a fallen star, but as a vulnerable figure, plagued by all manner of addictions and the ever-present ailments of someone of advancing age with a history of vices and self-destruction. The paradox was clear: the more human he appeared, the more mythical his image became. On the set of his home as much as on stage, Ozzy represented the eternal duality of horror: that which terrifies, but also that which arouses compassion. An endearing monster, both doomed and forever eternal.

Death as an Epitaph and Final Chapter

The announcement of his death in July 2025, just weeks after he had played his final concert with Black Sabbath in Birmingham, had the feel of a literary ending. It was as if fate had wanted the last note to resonate right where it all began, in the gray city of his childhood, the birthplace of heavy metal. The press would remember him with the titles that had accompanied him for decades: “Prince of Darkness,” “Godfather of Heavy Metal.” But what matters isn't the nickname, but what it embodies: the confirmation that Ozzy Osbourne transcended the realm of a musician to become a cultural symbol capable of appealing to people of all different ages, social backgrounds, and musical tastes.

His death will certainly never silence his voice: as with the great figures of horror movies - Dracula, Frankenstein, the Wolf Man - Ozzy will keep coming back again and again, summoned by his songs, by Sabbath's immortal riffs, by the howling of Bark at the Moon or by the disturbing murmur of Mr. Crowley.

Epilogue: Eternal Ozzy

Why did Ozzy seduce millions? Why was terror the key to his aesthetics? The answer most likely lies in the human condition. Horror, both in film and music, offers a ritual space to confront the repressed: the certainty of death that always lurks, the fear of illness, madness, or the fragility of the body. Everywhere society hides, Ozzy would expose. Everywhere the world sought to reassure, he invoked turmoil. Like the films that inspired him, his music served as a mirror and catharsis. The monsters were metaphors: the werewolf was addiction, the devil was guilt, and exorcism was the internal struggle against oneself. His concerts, like horror movie screenings, were collective communions of both fear and liberation.

Now that his voice has fallen silent, his echo still lingers. And that echo will continue to beat in Sabbath's monolithic riffs, in the bands that revere them, and in the young people who discover him as if they had stumbled upon a classic literary character to be explored and immersed in. Ozzy Osbourne was, and will continue to be, a flesh-and-blood, living legend of horror. Like the vampires from the old Hammer films, he has sunk into his grave only to resurface in our memories. Because art that dares to gaze into the darkness never dies: it transforms, like all monsters, into an eternal presence.

Previous content

Interview with Izabel PakzadNext content

Macedo: Twin Actresses, Musicians, and Producers