- Home

- Latest

- We remember Rossella Drudi

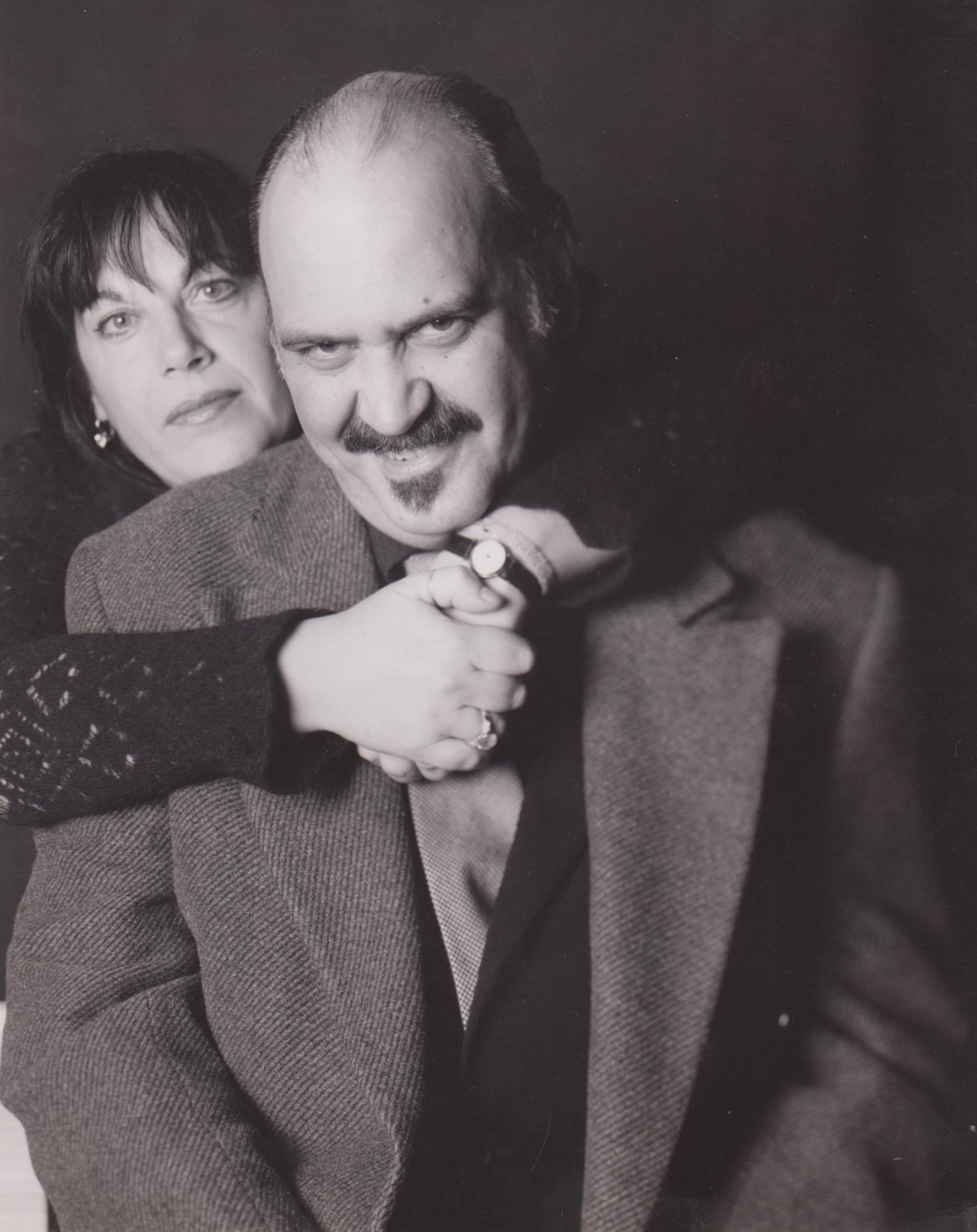

We remember Rossella Drudi

20 Feb 2025

Reading 28 min.

The Heroine of Italian B-Movies

A couple of years ago, I decided to revisit—or in some cases, discover for the first time—the vast number of films made together by Claudio Fragasso and Bruno Mattei. Every time I finished watching one, I would research the creative team behind it, and that’s when I realized that Rossella Drudi—Claudio Fragasso’s wife—was co-writing, and in some cases writing alone, the scripts for most of these films. Classics like Rats - Night of Terror (Bruno Mattei, 1984), Strike Commando (Bruno Mattei, 1986), Robowar (Bruno Mattei, 1988), or Terminator 2 (Bruno Mattei, 1989).

Drudi, who did a bit of everything on those shoots and also wrote Fragasso’s solo films, is a rara avis in 1980s and 1990s Italian horror and exploitation cinema: one of the few women who had a privileged place in a world predominantly dominated by men.

This in-depth interview with Rossella Drudi is a glimpse into the life of the person who wrote and helped bring some of our favorite films to life. And it is also a tribute to Drudi as one of the great figures of the golden era of Italian exploitation cinema.

To start, I’d like to ask you about your earliest memories related to genre cinema. What movies or series introduced you to fantasy and horror?

The first movie was Nosferatu by Murnau, the quintessential vampire. I feel a total fascination for this film. Even now, I get chills down my spine just thinking about it. After that, all the classics of horror cinema, especially vampire films and alien invasion stories, which I discovered thanks to film reviews in the 1970s.

And the first TV series was The Twilight Zone, the original black-and-white version. Then Belfegor, The Phantom of the Louvre, Il segno del comando, A Come Andromeda, Extra... all of them excellent productions from the 1970s.

While researching your biography, I discovered that you started as a screenwriter at just 12 years old, writing stories for Italian horror comics under the pseudonym "Ghibly." That’s incredibly young! How did you land that job? What were those comics called, and what do you remember about those years writing at such a young age?

Ever since I was a child, I fantasized about horror, mystery, and fantasy stories, and I even wrote them. I was a huge reader of comics and books—and I still am.

When I was twelve, I saw a notice on the cover of a comic book saying they were looking for horror stories, inviting readers to send in their tales by mail. I already had a story ready, so I sent it in. They liked it and published it, paying me a fee of 100,000 lire—that was it. I was so happy I couldn’t believe it; to me, it was just a game.

To make it more credible, I gave them the name and surname of an adult friend of mine. The pseudonym "Ghibly" came from an old comic whose name I don’t remember. I asked for anonymity, and they agreed. We never met; everything happened through postal mail.

The thrill of seeing my first comic published still gives me chills. The publishing house was based in Milan, but I don’t remember its name. At the time, there were many comics, and everyone worked really hard. It might have been a smaller house under Bonelli...

I also published serialized short stories for well-known Italian weekly magazines using the same process. At the end of the '60s and throughout the '70s, everything was easier and more possible compared to today.

Following up on the previous question, what are your favorite horror comics? Also, your favorite writers and illustrators?

As a child, I loved Diabolik, Satanik, Kriminal, The Thing, Mandrake, Superman, Tex Willer, Zagor, L’Intrepido, Il Monello, Il Corrierino dei Piccoli, etc. But my favorite was Diabolik by Angela Giussani and her sister—legendary writers and pioneers in a world that was entirely male-dominated.

As a teenager, I moved on to Il Mago, Alter Alter, Metal Hurlant, Eureka, Totem, Gli Argonauti, Linus, Cannibale, Frigidaire, etc. I also had many favorite authors, including Oesterheld, Moebius, Andrea Pazienza, Tamburini, Altan, Hugo Pratt, Crepax, Quino...

The Fetus stories were incredible, but I don’t remember the name of the author. Fetus was set in a world where no more babies were born due to a virus. The only survivor was this horrible, aged fetus with its umbilical cord still hanging: Fetus. A cruel murderer, loved and pampered by all adults. At night, he would go out with a large knife in his hand and, with great sadism, kill defenseless people, like homeless individuals or drug addicts.

It’s difficult to rank my favorite authors because they are all brilliant. In fact, I apologize if I’ve forgotten anyone. Unfortunately, nowadays, there’s only Japanese manga. They’re not bad—on the contrary—but young people don’t know about those artistic masterpieces from the 1970s.

After your experience as a comic book writer, at just 16 years old—still very young—you started working in the film industry as an editing assistant while still attending high school. Shortly after, you moved on to script supervision and writing dialogue for foreign series filmed in Italy. Those formative years must have been crucial for you. What did you learn about the profession during that period, and what foreign series did you work on?

It was a tough period, with a lot of work, and I was only 16. My boyfriend, who later became my husband and life partner, Claudio Fragasso, read my stories. He said he had no idea about my past publications, which I had kept secret from everyone, including my family. He told me I wrote well, so I decided to try writing screenplays.

I was excited, but I decided that first, I had to study and understand everything related to screenwriting, starting with editing, which is the backbone of a film. So in the afternoons, after school, I would go to the Cinemontaggio Piazza Zama Roma studios, owned by Otello Colangeli, one of the most important editors in Rome. I volunteered as an assistant. This meant I didn't earn a penny, but I learned a lot by working and meeting the right people in the industry.

In less than a year, I could do almost everything: numbering miles of film, editing sequences in slow motion, cutting, and more. While working there, I met various post-production supervisors who asked me if I could adapt film dialogues. With great boldness, I said yes, even though I had never done it before. But I had watched how it was done—"stealing" with your eyes is everything in this job if you stay alert—and I knew how to use slow motion.

They handed me the translated scripts of the series General Hospital (1973). I couldn’t make sense of the stories or the characters when they spoke; they sounded insane. That was because the literal translation into Italian made no sense. So, out of sheer youthful recklessness, I changed all the lines and even the story, carefully watching the lip movements to sync the dubbing. The editor didn’t notice and, on the contrary, told me I had done a great job.

I had fun—except with the boring TV Globo soap operas. I worked on many, until I finally had enough. I was nauseated.

You must have been exhausted!

Yes! But between 1980 and 1984, I returned to working on General Hospital, which had become even crazier. In the mid-'80s, I adapted the dialogues for the VHS release of The Omen saga and many other films.

By the '80s, I was working from home with a VHS player and cassette tapes instead of being in the editing rooms or Fonoroma de NC on Civinini Street, as I had in the '70s. Things were already changing, but unfortunately, still without contracts or recognition. The work was credited to the company hired for editing.

Later, I was also asked to supervise the dubbing of the films I had adapted. Another great learning experience—I learned how to adapt dialogues and coordinate voice dubbing, edit and reassemble films in pre-slow motion previews, make editing cuts, and prepare sequential scenes for the editor.

All of this tied me even more to the importance of screenwriting and its development, but it wasn’t enough. So I also had my first experiences as an editorial secretary, where I learned even more. A few years later, in the mid-'80s, I adapted the dialogues for all of Claudio and Bruno’s foreign films for various companies.

At the beginning of your career as a screenwriter, you worked as a ghostwriter. For example, in most of the films by the Bruno Mattei & Claudio Fragasso duo, you contributed to the script but were uncredited. How many commissioned scripts did you write?

My ghostwriter career started with Eduard Sarlui, whom I met at Fonoroma during a dubbing session. I wrote a large number of scripts for him, which he then assigned to young, inexperienced American directors. As he used to say: "They needed to gain experience."

I never met them, never saw them, and they never filmed in Italy. Sarlui was my only point of contact. The scripts and themes of those films were signed by him—sometimes under a pseudonym, sometimes under his company’s name. It was another mess, but at least Sarlui paid me well. All of them were genre films: war, horror, thriller, absurd comedy, adventure, fantasy, mystery, and Mad Max-style post-apocalyptic movies.

It was a true university of screenwriting for me. With Sarlui, I learned everything about foreign cinema, the international market, and buyers’ needs, which varied by country. Some requests were so strange that I might tell the stories one day… Later, the crazy trio was born: Bruno, Claudio, and me, working on some Italian coproductions with foreign countries. In 1979, the three of us wrote the script for Apocalypse Cannibal, but due to lack of funding, it wasn’t filmed as planned, which was a real shame. These films were made for theatrical release and cable TV circuits. The home video market only emerged years later, spreading worldwide. Many of these old films became cult classics and are still sold and reissued today. I’ve read many inaccuracies from people claiming these movies were direct-to-video and only meant for the Asian market.

That’s not true, then?

Not at all. Those films were sold worldwide at MIFED in Milan and the American Film Market in Los Angeles. They were highly successful because only Italian filmmakers of that era knew how to make movies in the American style: they were all shot abroad, with American actors, and in direct English language. They were low-budget films, accessible to buyers who couldn’t afford Hollywood productions. The direct-to-video market didn’t exist in Italy in the 1980s, and in the United States, these films were purchased for pay-TV channels. In Italy, all of these films were produced for theatrical release.

Why weren’t you credited as a co-writer?

The reason why my name doesn’t appear on some of these films is simple. At first, they didn’t want me to sign, always using the excuse of bureaucratic complications, but in reality, chauvinism prevailed, even though I had already written many scripts for Sarlui. Then there were issues with percentage distribution in co-productions. All of those films were co-produced with France and Spain (what was called the "tripartite" system) or with France and Germany, or even France and the United States. To receive funding and official recognition, each country had to have a certain percentage of authors. So they almost always sacrificed my name, replacing it with made-up names—sometimes French, German, or Spanish. Nonexistent people who were credited with writing the story and script.

You can check the credits of those films on IMDb to see for yourself. I don’t even know how many scripts I wrote without being credited... To count them all, I would have to add my work for Sarlui, the scripts for Filmirage, the ones for Flora Film, the ones for Production Group (Diego Alchimede’s company) and those for Ermanno Curti. But I also wrote for Tonino Valeri, Giannetto De Rossi, Massimo De Rita, De Concini, and many others whose names I no longer remember. I wrote six to eight films per year. Do the math…

When did your name first appear in the credits?

My name first appeared on screen thanks to After Death (1987), directed by Claudio and based on my script. It was also credited in Robowar (1987) by Bruno, which I wrote in the same year. That was also the year I wrote the scripts for Coop Game and Double Target. However, I had already signed other scripts under Sarah Asproon. But after working with Sarlui, I had a contract for all these scripts, which I still have today, proving that I am the author.

What is the origin of your American pseudonym, Sarah Asproon?

It came from my first screenplay. It was 1985, and I wrote an erotic comedy for Aristide Massaccesi, producer of Filmirage, whom I met through Sarlui. The film was Eleven Days, Eleven Nights, shot in 1986. The movie was fully financed by Sarlui, but he didn’t want to be credited. When Aristide sent me the contract, the notary told me I had to use an English name because the movie needed to be 100% American.

With no time to come up with one and feeling shocked by the bitter surprise, I ended up signing with the same name I had given to the protagonist of my story: Sarah Asproon. According to the contract, I wrote the script, but that’s not all… Since I didn’t have a tax number, they credited Claudio as the screenwriter, even though—as he has repeatedly stated—he never wrote it. After that, I kept using this pseudonym for other films. I remember my surprise when I found out that the Germans wanted to meet the real Sarah Asproon. In Germany, the film had caused a sensation. Aristide had told them it was a true story—he was laughing at me. And the Germans are still waiting for Sarah’s book about her hundred lovers...

The day I signed the contract for Eleven Days, Eleven Nights, Michele Soavi was with me.

He had just debuted at Filmirage with his film Aquarius.

I remember that when we left the notary’s office, we were both sad, I because once again, I wasn’t able to sign with my real name, he because he had lost his film—it was no longer his; he had sold the rights.

What a story…

Do you think the Italian SIAE (Society of Authors and Publishers) ever paid me royalties for that film? They claim that I never appeared at the Ministry, even though I sent the original film contract and proved that Sarah Asproon and Rossella Drudi are the same person. And it’s a shame, because that movie was a huge success in theaters across Europe, and later, on cable television and VHS. Just think—in London, people were lining up in front of the cinemas to see it. And in Rome, at the Nazionale and Quattro Fontane cinemas, I saw with my own eyes that the theaters were packed. People loved the movie, they laughed a lot and really got into the story.

One of my favorite films from the Mattei-Fragasso duo is The Other Hell (Bruno Mattei, 1981), which brought new life to the nunsploitation subgenre, blending it with influences from Carrie (Brian De Palma, 1976) and The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973). In the film, your and Claudio’s daughter, Elisa, appears as a baby, co-starring in one of the wildest and best scenes in The Other Hell.

I really like that film too. But I need to clarify something: That film wasn’t directed as a duo.

Its original title, L’altro Inferno, was entirely directed by Claudio. Meanwhile, at the same time and in the same locations, Bruno was shooting La Vera Storia Della Monaca di Monza. I wrote the script for L’altro Inferno in 1980, while Claudio wrote the script for La Vera Storia Della Monaca di Monza with Bruno. Basically, there were two mini-crews that often swapped roles depending on shooting needs, and I must say that Claudio and Bruno helped each other a lot. Both films were shot inside a convent of French nuns, which today houses a police station, and also inside the Orsini Castle in Frascati.

What do you remember about that cameo, and how was the filming of that scene? What did your daughter say when she watched the film later in life?

At the time, my daughter was only three months old. The scenes with her were shot in the castle’s kitchen. I remember it was freezing, so I stayed with her in a heated room and only went to the set when everything was ready to shoot. She was a very calm baby, always asleep, but when she was passed from my arms to Franca Stoppi’s, she suddenly burst into uncontrollable crying. She must have felt the adrenaline of that incredible actress. I had to calm her down before we could shoot. Everything went fine—until Claudio wanted to get a close-up of her blue eyes. But Valentina had fallen asleep!

I told Claudio, "Don’t you dare wake her up!". So he was forced to use a close-up of a doll’s eyes instead. The same doll that was later thrown into the boiling pot. When she grew up and saw the film, she told us that we were two reckless fools, but she had a great time watching it.

By the way, here’s a fun fact I’ve never shared before: The clothes my daughter wears in the film are authentic baptismal garments from the early 20th century, belonging to my mother’s family. They originally belonged to her brother, my uncle.

Your collaboration with the duo was crucial. In fact, rather than a duo, I like to call it the Mattei-Fragasso-Drudi trio. What was it like filming with Bruno Mattei, and how was his chemistry with Claudio?

The three of us had a great time writing together. Bruno was practically always at our house—you could say he lived there. I met him in 1979, but Claudio had already worked with him on two films before that. Our first script together was Apocalypse Cannibal, written in 1979.

Bruno was a cultured and fun man, especially passionate about ancient history and the fall of the Roman Empire. He was an incredibly skilled film editor—you could only learn from him. But Bruno and Claudio were totally different, Bruno didn’t like actors and refused to talk to them; Claudio, on the other hand, directed them constantly—both their movements and their acting. Their filming styles were also different, Bruno loved long shots, open spaces, and actors filmed from afar; Claudio preferred close-ups, mid-shots, and detailed framing. But together, they balanced each other perfectly, forming a fantastic team on set.

I knew them both very well, I knew how to write for one and for the other, and I think I’m the only one who can tell which scenes were directed by Bruno and which by Claudio within the same film.

Regarding your chemistry, what was it like working on films such as Robowar or Strike Commando?

In Robowar, Bruno wanted a mix between Predator and RoboCop, just as Terminator 2 was a mix of Aliens and Terminator. Meanwhile, Strike Commando and its sequels were supposed to be a sort of Rambo, but with an ironic twist. Bruno never took himself seriously as a filmmaker. He loved exaggeration, especially with endless, over-the-top shootouts and Reb Brown screaming like a lunatic—something that eventually became his signature style.

He had fun doing it. I remember how he would laugh during those takes, and later, he would also laugh while watching them in slow motion in the editing room. At the time, Claudio preferred more theatrical and restrained compositions, but he also played with irony, just in a different way. For example, in Strike Commando, there's the final attack scene where, after an explosion, the Russian's false teeth fly through the air and land in the protagonist's hand—that was Claudio’s joke. The chemistry was perfect, both with Bruno and Claudio. I had a great time working with them. Sometimes, during script meetings, we would argue loudly, only to end up bursting into laughter when we found a solution that satisfied all three of us.

For example, I didn’t want to copy Aliens and Terminator so blatantly for Terminator 2, so I came up with the Venice sequence to give the film a slightly different feel. Bruno accused me of being a snob, but he was laughing at my decision. He never took himself seriously—he was just playing, and he didn’t care about anything else.

And what about filming in the Philippines? I imagine you had little time and tight budgets.

Filming in the Philippines with a limited budget was not much different from filming in Spain or Italy under similar conditions—sometimes, we had even less time and money there.

Claudio and Bruno were never lucky enough to work with normal budgets.

But they were fast and skilled. They managed to shoot two movies in the Philippines in the time it would take to shoot one. In conditions that were beyond precarious—sometimes absurd and even dangerous.

But they had fun, and the jungle didn’t scare them. They even filmed during typhoons, flying in helicopters at the risk of dying, while watching an entire village disappear underwater. That’s the madness of filmmaking. Or when cobras escaped into the jungle. That happened during Born to Fight (Nato per combattere), starring Brent Huff, written in 1987 and filmed in 1988. The crew banged bamboo sticks together to scare the snakes away. Or when a canoe carrying Claudio, Ottaviano Dell’Acqua, and the camera operator broke loose from the shore and got caught in the rapids, heading straight for a 20-meter waterfall. They were rescued at the last moment by a group of Filipinos who jumped into the water and pulled them back to safety.

In short: total recklessness and zero safety measures. Luckily, everything always turned out fine. The heat was unbearable, day and night, with 100% humidity. Some members of the Italian crew were passing out like flies from the heat. I remember the great relationship between Claudio and actors like Miles O’Keeffe, Donald Pleasence, and Bo Svenson in Double Target. The legendary Richard Harris in Strike Commando 2, with Brent Huff as the lead. Brent was a nice, friendly guy—very professional. What can I say? We suffered, but we had a great time—true pioneers with a spirit of adventure.

By the way, what can you tell us about Flora Film and Franco Gaudenzi, the producers of most of the films you worked on in the 1980s? Was it easy to work with them?

I can only speak highly of Franco Gaudenzi. He was a smart, kind, and energetic businessman, but above all, a friend. He was full of ideas, enthusiasm, and projects. Super busy, even now, yet he always managed to find a few minutes for every need. I worked a lot for him, with and without Claudio and Bruno, on other films, such as Filmirage productions by Aristide Massaccesi, and also for Rai 1, like the drama Appuntamento a Trieste, starring Tony Musante.

At Flora Film, located on Via Nomentana, I had my office and my first computer.

There was no Internet yet, but I taught myself how to use it, as always. It was an Italian IBM computer, and my beloved typewriter was sent to the attic. I owe my deep knowledge of the foreign market to Franco and Mariella Tuccio of Variety Film (now Variety Distribution S.r.L.). Claudio and I often accompanied them to Mifed in Milan and other film markets. During those experiences, we invented a much more effective method than traditional brochures for selling films in pre-production. In the 1980s, we went to Luciano Vittori’s factories, the first in Rome to have computers with 3D graphics programs, used for television networks of the time. We took snippets from each film and pre-edited them into a kind of trailer. At the time, avant-trailers and showreels were more common, but they were longer. After finding the right graphics, we invented filmed brochures, complete with a voice-over by one of the best dubbing actors of the time, a friend of ours.

He would "perform" the brief synopsis of the plot. No one had ever done this before, and it was a success at Mifed. So much so that other producers asked us to do the same for their films. Too bad we didn’t patent the method—artists make terrible businessmen. What else can I say? He and Mariella are still a wonderful couple, in work and in life, like us, and our friendship has lasted through the years!

The most memorable films from the Mattei-Fragasso-Drudi trio were based on American hits like First Blood (Ted Kotcheff, 1982), Predator (John McTiernan, 1987), The Terminator (James Cameron, 1984)... Italian exploitation at its finest. As the author of some of the original stories that became screenplays, did you take those American films into account when shaping your script treatments?

Bruno watched the original films over and over again on VHS, rewinding and fast-forwarding. He wanted to copy the dialogues word for word, but I refused. Instead, I inserted my own stories and plotlines. Then, once on set, he did whatever he wanted.

There’s an Italian supporting actor I’m particularly a fan of. His name is Luciano Pigozzi, a staple of Italian B-movies, and he appeared in several Mattei-Fragasso films, such as the excellent Double Target (Bruno Mattei, 1987) and Strike Commando. What do you remember about Luciano, and what was it like working with him?

Luciano Pigozzi was a great person. I mainly knew him as a production assistant on all those films shot in the Philippines. Luciano had lived in Manila for years. He had set up his own company, which provided everything a film crew needed. I knew that he had been a good actor in the past, but in our films, he mainly worked in production and occasionally played small roles.

Even though there were other female screenwriters in Italian B-movies, like Elisa Briganti (Dardano Sachetti’s wife) and Olga Pehar (Umberto Lenzi’s wife), none of them had a career as long as yours, which expanded into other genres and media. In fact, there are very few women worldwide with such a strong résumé in genre cinema. You are a pioneer, and in my opinion, a role model. Do you see yourself as a pioneer in opening doors for women in genre cinema?

I don’t see myself as a pioneer, because I find it absurd that genre cinema should be restricted to men. I have always felt equal to everyone else. Everyone should be free to write whatever they want, as long as they have ideas, creativity, and imagination. It’s a job you can’t learn—only refine technically through study. If you don’t have innate talent and curiosity, you can’t do anything. But I can say that I had to fight three times harder than a man to be recognized, To earn respect and credibility, to write what I wanted, without external impositions (except in the beginning), to gain negotiating power.

Everything I achieved, I fought for myself, conquering each step with effort and determination.

Claudio never helped me with that. From the start, he told me: "It’s up to you to prove your worth." So, if I got a good contract, I worked; if not, I didn’t. Unfortunately, women still have little credibility in this field, especially in genre cinema. This is partly due to narrow-minded producers who still believe that a woman can only write romance stories or light comedies—which I can’t stand. I love cinema in all its forms, whether intense and gritty or pure escapism.

I like keeping the audience glued to their seats, whether it’s a fantasy thriller or a true story. I think I achieved that with Teste rasate and Palermo Milano solo andata, where audiences left the theater feeling like they had been inside the car with the characters. Also with Coppia omicida (1998, written in 1996), which anticipated today’s technological isolation through a couple’s communication struggles during a marital crisis.

Or with Concorso di colpa (2005), where I explored the failure of ideals among a group of left-wing militants from the 1970s who, as adults, chose to preserve their careers and social status rather than their principles. A film even more relevant today than it was then. Or with La grande rabbia (2014), which depicts the economic, moral, and ethical crisis in Italian suburbs, as well as political corruption. I write what I feel and what I see. What I love and what I need to express, in my own way. That’s all.

Regarding the previous question, did you have any friendship or contact with Elisa Briganti and Olga Pehar? You were infiltrating a male-dominated world!

I never met them, but I’m glad they were there. Maybe I crossed paths with Dardano’s wife in one of the many meetings we had, but I’m not sure. I’ve always worked directly with the producers, and I never felt like I was infiltrating a male world. For me, the producer is my employee—I propose the stories to be made. Then, they decide whether to produce them or not.

The world of Italian exploitation cinema was mostly male-dominated. Did you ever feel intimidated by it or experience discrimination because you were a woman (sexism or unfair treatment)?

The biggest discrimination was not being able to sign my scripts and being offered much lower pay than my male colleagues. But I fought tooth and nail with determination and eventually achieved my goal. Those who initially discriminated against me later changed their minds once they got to know me. Those who don’t know me still think they are better than me—just by birthright. But they don’t even have a third of my filmography on their résumés. In 1986, for the first time, I worked on set not as an editing secretary but as an on-set screenwriter.

I helped actors with their performances, character studies, and interpretations. I believe I was the first in history to do this. Now, some other women do it too, but back then, no one knew how to define my role. So, at first, they listed me as an assistant director. Later, my job became recognized as a real profession, and it deserved proper pay and credit. In the U.S., this role is called an Art Director, because the person not only works with the actors but also supervises all departments as the script’s author. In Italy, the Art Director is the set designer, so there was confusion. Now, the role is called "Actor Coach", but that’s still not quite right.

However, it exists.Some producers say I was always ahead of my time. Maybe that’s true, but for me, it was simply natural to do so. I participate in location scouting and every phase of film development. That’s essential to writing a good script. I also love working with actors, first one-on-one, then as a group, like in theater. On set, the director wants actors ready to go, with less and less prep time due to budget constraints, so this work is crucial.

Lately, companies like Severin Films and 88 Films have been releasing restored 4K and 2K versions of the films you made with your husband and the Mattei-Fragasso duo. In fact, these films have never looked better—they look even better than when they were first released. Do you agree?

Yes, I agree. I met David Gregory and his business partner, Liz, another wonderful couple in both life and work. They run Severin Films together with two other partners. They are fantastic people, just as passionate and in love with cinema as we are. They have done an amazing job with many of our films. They have remastered the original movies and enriched them with many extras, such as our interviews and more. We are very happy with their work, and I will never stop thanking them for it. We have attended several horror conventions in the U.S. together, where we were treated like stars by thousands and thousands of enthusiastic fans.

These releases are being met with enthusiasm and love from fans. How does this renewed appreciation and affection for your films make you feel?

I feel very happy and proud, as I said before... But these things can’t be understood unless you experience them. Imagine huge crowds cheering and thanking you while we thank them in return. At every screening, the same incredible atmosphere— It’s deeply rewarding after everything we’ve been through.

Of all the films from the golden age of Italian B-movies—from the late '70s to the early '90s—that you worked on, which three are your favorites, and why do they hold a special place in your heart?

I can’t answer this question. Every story is a birth, and a birth is like a child. And as they say in Naples, "I figli so' pezzi 'e core"— Emotionally, all films are equal to me. But there is one film from 2010, directed by Claudio, that is very important to me: Le ultime 56 ore. This film is about depleted uranium used in the bullets during the Balkan War. Many soldiers developed leukemia as a result, as well as many civilians affected by the war. Many have died, and many others are still sick. The Italian government was aware of the danger, as the Americans had already warned about the risks. But our soldiers were not informed and went into battle without any protection, just like other European soldiers.

The Italian Ministry of Defense requested a private screening of the film before its release. We had to go—Claudio, the producer, and I. We were very worried, as the theatrical release was just days away. After the screening, they asked us to cut some scenes and alter certain dialogues. If we didn’t comply, we could have problems—it wasn’t a direct threat, but the message was clear. The producer was terrified and forced us to make those changes. Additionally, they added a message at the end of the film thanking the Ministry of Defense for their support. The final text also stated that the Ministry of Defense had approved and recognized compensation claims for the sick soldiers and the families of those who had died.

But none of that was true—even today, many soldiers are still fighting for justice. You can imagine how much I suffered from this manipulation. I knew we were going up against the arms industry, but I didn’t know the full extent of it. Unfortunately, the press, often superficial, read the final message and, instead of investigating or asking us, accused us of ambiguity. So in addition to being deceived, we were also discredited. However, the film did very well abroad. In 2012, the European Commission selected it as the best Italian film to represent Italy at the European Film Festival. Every year, this festival selects 24 European films focused on civil rights issues. This is the only film that addresses the dangers of depleted uranium. But it’s not a documentary—it’s a film with a strong, hard-hitting story, built around a thriller narrative (which is always present in my stories), with spectacular action scenes and high adrenaline.

Currently, Claudio and you are in post-production with a martial arts film titled Karate Man. What can you tell us about it?

Unfortunately, COVID-19 delayed the film and then slowed down the entire post-production process. We have many special effects in the movie, and that has been the main challenge. But now, the process has resumed, and I hope it will be finished by late October [2020] or, at the latest, November [2020]. I can tell you that it is a love story dedicated to pure karate—the ancient karate, as both a feeling and a philosophy of life. There is also a bit of real-life history about the protagonist, which inspired me greatly. I can’t reveal the plot, but I can say that there will be never-before-seen footage of the world of karate competitions, featuring real champions who have won world titles multiple times.

Claudio invented and experimented with new filming techniques to make the fight sequences unique. This film is an example of how pure sports can help people dealing with specific health conditions, and how a man who believes he is finished can rise again and triumph, thanks to his love for sports and the strength of true friendship.

Claudio’s first film as a director, Passaggi (1978), was funded with the money you collected at your wedding. That means you’ve been together for over 40 years, both personally and professionally—a very difficult achievement. What’s the secret to maintaining such a long and fulfilling relationship in both love and work?

Yes, we have been married for 41 years. May 20, 2020, was our anniversary. But we’ve known each other since I was 14. At the time, I didn’t like him at all—in fact, I found him annoying! Funny, isn’t it? There is no recipe or formula for a lasting relationship. I believe we were lucky to find each other, recognize each other, and choose each other.

We grew up together, sharing all kinds of experiences, both good and bad. We’ve been through so much together that you wouldn’t believe it. But when there is love, everything can be overcome. It’s too easy to stay together when everything is going well. It’s the tough trials in life that either strengthen or break a relationship. We also shared the same passion and love for cinema, and we met at a film club. We have never missed a single movie in any stage of our lives. At first, we didn’t have the same profession.

I was in high fashion, working with my parents. I designed clothing and accessories, which my parents produced for major fashion brands. But Claudio always involved me in his work, even if only indirectly. He needed my advice and opinions. Then, when we finally shared the same profession, it was no longer just a job—it was a true passion. That made everything easier. At home, we spoke the same language, and that helps a lot. So, when we got married, we asked our friends not to give us gifts. Instead, we asked for money to fund Claudio’s first film: Passaggi.

Lastly, do you follow current horror and fantasy cinema? If so, what are your favorite films from recent years?

Of course! Even though I’m a cinema omnivore and watch everything. I don’t differentiate between genres, only between good and bad movies. In recent years, when it comes to horror, it’s increasingly difficult to find good films. Most of them are all the same, with little originality and too many CGI effects. They don’t scare anyone. But I have seen some interesting films…

I love movies that still respect the classic gothic horror and thriller atmosphere. For example, The Sixth Sense—I consider it a masterpiece. I also loved the entire Insidious saga, especially the first and the last one. From Northern Europe, I loved Let the Right One In, and some others whose titles I can’t recall right now. I also really enjoyed Get Out. But I didn’t like Jordan Peele’s second film, Us, at all. Such a shame! It lost all the charm and narrative impact that Get Out had. Other films that I found less impactful but still acceptable: Mama, The Witch, The Invisible Man.

I can’t remember all the titles right now… But I really dislike movies that feel like amusement park haunted house rides. The ones that only scare or entertain three-year-olds, without an ounce of story behind them. But there is one TV series that surpasses all of them by a thousand points: Breaking Bad. I have watched it a thousand times. It is absolutely untouchable—the masterpiece of masterpieces. No grey areas. It’s impossible not to love this series. The character development, their psychological depth, and how they evolve based on the circumstances life throws at them—all of it is perfectly written. The dialogues feel natural, never forced. The direction is mind-blowing. It’s insane!

By Xavi Sánchez Pons

This interview is taken from issue 35 of El Buque Maldito fanzine.

Previous content

Interview With Enrique BuleoNext content

Interview With Nacho Vigalondo